The State Monad

Motivation

Throughout our time spent programming and coding more logical shapes, we inevitably encounter the same patterns over and over. In particular, we often find ourselves keeping track of state throughout long sequences of functions. For instance, the state can literally be same finite state machine that our program acts under, but as developers of our program, we focus more instead on the interactions with the state machine than the intricacies of the machine itself.

The State monad abstracts over these tedious bookkeeping details of the state, allowing us to think at a higher abstraction while being confident in its correctness.

Defining the State Monad

The State monad is roughly defined as follows.

Instead of being some object encapsulating state,

it is a function processing some input state s whilst producing the output a.

newtype State s a = State {

runState :: s -> (a, s)

}

Using the type s -> (a, s) is a bit weird.

Why use this particular definition?

We want to split our desired computation and create a distinction between computation on the state level and that above it.

If our state is embodied by a finite state machine, then the state level subsumes keeping track of current state and state transititons.

The higher-level abstracted computation involves the desired computation that interacts with and builds upon the state machine.

Ultimately, computation on the state level is deemed “boring” and “irrelevant” to the ultimate intent of the program.

Naturally, we want to focus on that higher more abstracted computation than the bookkeeping of the state.

However, without some involvement of the state s, we can never have any concrete execution of logic.

When modeling the non-state computation, the best we can do is to design a function that take the state s as a parameter

and return the new value and state.

The type s -> (a, s) embodies this paradigm.

What if we have computation that requires an input besides state?

i.e. Something of type (a,s) -> (b, s)

If we were programming in a language like cpp, we may declare the function of type (a,s) -> (b, s) like so:

/* returns (new_state, b) */ std::pair<State, B> compute(State current_state, A a);

In Haskell, we can take advantage of higher order functions.

Through currying1, we can obtain a -> s -> (b, s), which can be aliased as a -> State s b.

Practically, (a,s) -> (b,s) and a -> State s b embody the same energy, but we will favor a -> State s b.

We will see more concrete examples of these in future examples.

Example: Finite State Machine

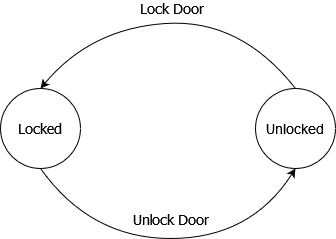

Let’s look at an example of the state monad with the following finite state machine.

import Control.Monad.State

-- A door can either be locked on unlocked

data LockState = Locked | Unlocked deriving (Eq, Show)

-- `DoorState` will be the underlying state used for this example

-- It keeps track of the door state and the number of entries into the door.

-- The specific monad we will use is `State DoorState a`,

-- where `a` is the type parameter.

data DoorState = DoorState

{ lockState :: LockState

, entries :: Int

} deriving (Show)

-- We can get and set the the underlying state with the following functions

-- get :: State s s

-- get = State $ \s -> (s, s)

-- put :: State s ()

-- put new = State $ \_ -> ((), new)

-- Lock door if not already locked

lock :: State DoorState ()

lock = do

s <- get

put s{lockState=Locked}

-- Unlock door if not already unlocked

unlock :: State DoorState ()

unlock = do

s <- get

put s{lockState=Unlocked}

-- Enters door if possible while keeping track of number of successful entries

enter :: State DoorState Bool

enter = do

s <- get

let suc = lockState s == Unlocked

if suc then

do

put s{entries=((entries s) + 1)}

return suc

else

return suc

getEntries :: State DoorState Int

getEntries = do

s <- get

return $ entries s

Here, we define functions that can read and modify the underlying state.

Finally, the functions enter and getEntries behave differently depending on the state,

showcasing how the underlying state can influence computation.

After defining all these functions, we can finally see the state monad in action sequencing computation.

main = do

let -- sequence functions together

computation :: State DoorState Int

computation = do

unlock

enter

lock

enter

enter

unlock

enter

enter

enter

getEntries

let init_state = DoorState Locked 0

-- run computation with `evalState`

putStrLn $ "running computation: " ++ (show $ runState computation init_state)

-- use `execState` to obtain final value while dropping state

putStrLn $ "num entries: " ++ (show $ evalState computation init_state)

-- use `execState` to obtain state while dropping the final value

putStrLn $ "final state: " ++ (show $ execState computation init_state)

running computation: (4,DoorState {lockState = Unlocked, entries = 4})

num entries: 4

final state: DoorState {lockState = Unlocked, entries = 4}

The magic of the state monad occurs when we sequence functions. When we sequence the functions monadically, all the state transition logic happens under the hood.

-- The passing of the underlying state happens under-the-hood, allowing

-- us to focus on a higher level of abstraction.

computation = do

unlock

enter

lock

enter

enter

unlock

enter

enter

enter

getEntries -- return final number of successful entries

Inside the State Monad: How does it work?

Recall that a monad is defined by two methods: return and >>=(AKA bind).

For the state monad, return is defined simply as

return :: State s a

return a = \s -> (a, s)

This wraps the value a into a monadic one to be sequenced,

and when we do sequence functions together,

return a simply injects the value a into the computation chain.

e.g. return a >>= computeWithAProducingB >>= computeWithBProducingC

As with other monads, the inner clockwork upholding all the magic lies with the bind method. Let’s take a peek at how it’s bind is defined for the state monad starting with its type signature.

(>>=) :: State s a -> (a -> State s b) -> State s b

State s a is a function of type s -> (a, s); it takes an initial state and produces both an output value and some new state: (a, s).

The final output State s b is also one function producing some output and state.

The second parameter, being a higher-order function, is a bit more complicated.

On input a, it produces a function of type s -> (b, s).

Put differently, on input a,

the function a -> State s b produces different deterministic computation.

As mentioned in the introduction, this can be thought as the uncurried version of

the function of type (a,s) -> (b,s)

Noteworthy observations:

- The specific value

athat we desire to be used witha -> State s bwill be produced byState s a. - Since the overall state may be changing throughout our computation, we have to take care to pass it correctly from

State s atoState s b. - Since the final output

State s b(AKAs -> (b, s)) is a function,

we are not actually performing any computation, but rather just composing them properly to produce the correct determinstic computation when we eventually have some valid input state.

(>>=) :: State s a -> (a -> State s b) -> State s b

-- below, `bind'` differs from (>>=) in that we remove some boiler plate syntax

bind' :: (s -> (a, s)) -> (a -> (s-> (b, s))) -> (s -> (b,s))

bind' mkA mkBfromA = \input_state ->

let (a, tmp_state) = mkA inputState in

(mkBfromA a) tmp_state

The above definition of bind satisfies our criterions:

bind' mkA mkBfromA = \input_state -> ... -- The final output is a lambda; we do no computation

(mkBfromA a) -- we use the constructed value `a` to produce the correct function `State s b`

(mkBfromA a) tmp_state -- we pass the temporary state produced by `State s a` to `State s b`

Succinctly, >>= is defined as

(>>=) :: State s a -> (a -> State s b) -> State s b

(>>=) m f = State $ \s ->

let (a, s') = runState m s in

(f a) s'

Example: Carrying RNG as state

Since functions in Haskell are pure, functions returning random values must

take a random number generator as input.

If we wanted to produce two random integers, we resort to passing the RNG around.

getTwoRandomInts :: StdGen -> (Int, Int)

getTwoRandomInts g =

let (a, g') = random g

(b, _) = random g' -- tedious to carry g' here

in (a, b)

Since this is obvious tedious and uninteresting, handling RNG passing is a good candidiate to wrap within the state monad.

import System.Random

import Control.Monad.State

-- produces a random int in the range [0,5]

getRandomInt :: State StdGen Int

getRandomInt = do

g <- get

let (num, g') = randomR (0, 5) g

put g'

return num

-- Adds a random value to the input

addRandomInt :: Int -> State StdGen Int

addRandomInt x = do

y <- getRandomInt

return $ x+y

main = do

gen <- getStdGen

-- magic here

let compute = getRandomInt >>= addRandomInt >>= addRandomInt

putStrLn $ show $ runState compute gen

From our earlier discussion on the motivating the state monad, we wanted to split the computation into the boring state portion and the more useful abstracted computation.

In this example, the passing of the RNG through the monadic bind serves as the state computation.

The production of random values and adding them together into a final accumulated

value is the abstracted computation we care about.