R-Values and L-Values

Special Thanks

Special thanks to BHang, KFang, and EZhang for providing the much needed motivation and encouragement for this post.

Motivation

If you ever want to intimidate non-cpp programmers, just start a discussion on r-values and l-values. That’ll surely scare them.

However, this puts us a precarious position if we ever encounter someone who knows what a funny r-value is or if we ever try to explain what an r-value is, so we better learn how they work.

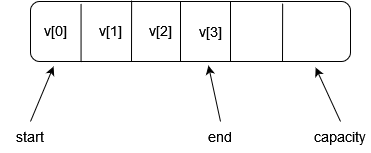

Vector Anatomy

In cpp, the standard container representing a dynamically sized contiguous array of objects

is std::vector. For those unfamiliar, vector’s usage and ubiquity matches that of

python lists or java arraylists.

vector<int> v;

for(int i=0; i<1'000'000; i++)

v.push_back(i);

The above code snippet depicts a vector of integers being created and populated with the first 1 million integers. With this many integers, how big should we expect the vector to be?

sizeof(v) // returns 24

This is a bit surprising at first given that we just populated the vector with a million integers, however a quick look at the underlying vector implementation should clarify everything.

The vector container holds just 3 pointers: start, end, capacity.

When we computed sizeof(v), we only obtain the combined sizes of these pointers: 24.

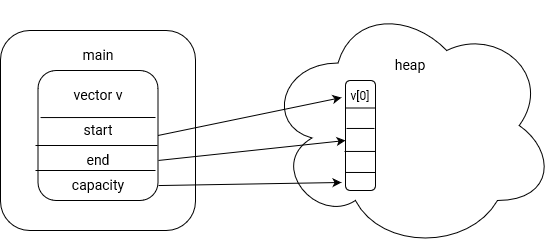

The Stack and the Heap

Now let’s see how this works in conjunction with the process memory layout. Consider the code snippet below.

int main(){

// Construct vector

vector<int> v;

for(int i=0; i<1'000'000; i++)

v.push_back(i);

}

The space allocated for the vector data exists on the heap instead of the stack. This implementation allows for dynamic resizing without altering the amount of space needed on the stack. How intelligent.

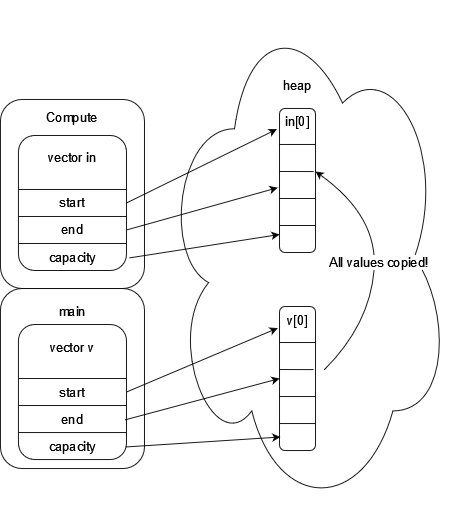

Passing Arguments

Let’s build upon our example with a new function Compute.

We would like to look into how the vector is passed as a parameter.

void Compute(vector<int> in) {

// computation with in

}

int main(){

// Construct vector

vector<int> v;

for(int i=0; i<1'000'000; i++) {

v.push_back(i);

}

// perform computation

Compute(v);

}

When we call Compute, every value within the vector v is copied

to create vector in.

Whether this is optimal depends on the context.

However, suppose we meet certain conditions:

Computerequires its own copy of the vector and may modify it. This disallows changing the method signature to use const reference.- The vector constructed in

mainis solely used forCompute. In this case, having two copies of the same vector in the heap is unnecessary is expensive and should be avoided if possible.

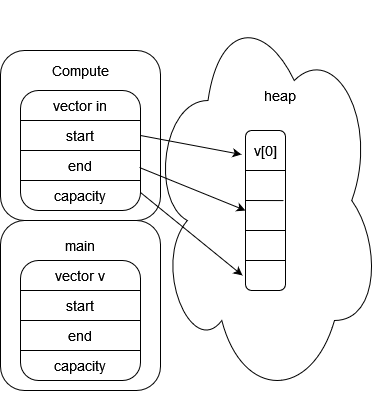

// perform computation with `std::move`

Compute(std::move(v));

The above change incorporating std::move does exactly what we want. No copies at all.

The internal pointers inside v are copied to those for parameter in,

so we have passed the vector as an argument without copying its entire data.

Compute now owns the vector and can modify it however it sees fit :)

Notice that the pointers within vector v in main are invalidated.

Using this value, or any value after moving it,

is not recommended and may cause undefinied behavior1.

R-values

We have seen how we can optimize copies of data by coping pointers instead of copying all the data, but we still have not tackled the crucial question: What exactly is an r-value?

Historically, r-values are named as these values tend to be on the right side of the equal sign,

whereas l-values are on the left.

i.e. auto lvalue = rvalue{}

Ok, now that we understand everything, we can all go home.

If only it were that easy.

Value Category Taxonomy

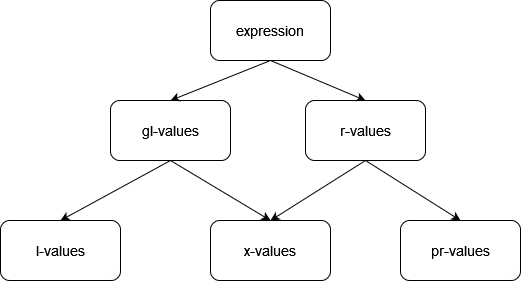

Each cpp expression has a value category. On the finest level, they are: lvalues, xvalues, and prvalues2.

From the diagram, r-values are a superset of both x-values and pr-values.

gl-values are a superset of l-values and x-values.

- gl-value (AKA: Generalized l-value) - determines the identity of an object.

One general guideline: if you can take the address of it, it’s a gl-value. - pr-value (AKA: Pure r-value) - initializes an object. Typically a temporary.

e.g. The following initializer list is a pr-value

vector<int> v = {1,2,3} // {1,2,3} is the pr-value - x-value (AKA: eXpiring-value) - a gl-value that can be reused.

e.g.std::move(v)in our earlier example is anxvalue - l-value - a gl-value that is not an r-value

std::move

Contrary to its name, std::move performs no computation.

std::move sole purpose is to cast the value to an r-value.

This can also be done manually with static_cast; std::move is just more convenient and ergonomic.

Once an object has been cast to an r-value, we can optimize computation with the

appropriate function overloads.

Function Overloads

// relevant vector constructors

vector(const vector& other); // const l-value ref

vector(vector&& other); // r-value ref

The && signifies that the argument is an r-value reference, so the function

vector(vector&& other); can only be called by r-values.

Attempting to construct a vector with a non-rvalue would invoke the

vector(const vector& other); constructor.

Even though vector(const vector& other); can theoretically also take r-values,

r-values will always invoke the r-value reference overload.

In the example with vectors, we use the move constructor vector(vector&& other);

When we construct the parameter vector in, this move constructor is being invoked to copy the

internal pointers and not the values on the heap.

Limitations and Caveats

Moving is just an optimization and is not free.

- Not all types support moving.

For instance, astd::arrayin local scope will always live on the stack, so there are no pointers to data to copy. We can always cast an array to an r-value withstd::move, but a copy will still be performed as there is no r-value ref overload for the array constructor. - Moving may not be cheap.

Consider a smallstd::string. With small string optimization(SSO), the entire string will live on the stack, so in this case there are also no pointers to copy. Even though we may be invoking the correct move constuctor, we do not actually save on computation as the entire string will still have to be copied