The Least Squared Solution in Linear Algebra

Motivation

Suppose we are trying to solve the equation \(Ax=b\). If \(b\) is in the image

of \(A\), then the solution is simply \(x_p + N(A)\) and we are done.

However, if \(b\) is not in the image of \(A\), we are kind of stuck as no

solution exists.

It may still be useful to find the best value \(\hat{x}\) that minimizes

the squared distance between \(A\hat{x}\) and \(b\).

If you have gone through a basic linear algebra course, you may recognize the

solution:

This post serves to better understand the logic behind that equation.

Linear Algebra Review: The Four Fundamental Subspaces

Suppose we have some matrix of real values \(A\).

\(A\) represents a linear transformation \(\mathbb{R}^n\to\mathbb{R}^m\)

There are 4 fundamental subspaces associated with \(A\):

-

\(C(A)\)

The column space \(A\) is the span of the columns of \(A\) and lives in \(\mathbb{R}^m\) -

\(N(A)\)

The null space (or kernel) of \(A\) is all \(x\) such that \(Ax=0\). It is a subspace that lives in \(\mathbb{R}^n\) -

\(C(A^\top)\)

The row space of \(A\) is the span of the rows of \(A\) and lives in \(\mathbb{R}^n\) -

\(N(A^\top)\)

The left null space of \(A\) is the set of all \(y\in\mathbb{R}^m\) such that \(A^\top y = 0\). Notice that this subspace lives in \(\mathbb{R}^m\).

Of the four, the column space and nullspace are probably more familiar to the typical math student; however, the row space and left null space are still important.

\(C(A)\) and \(N(A^\top)\) are orthogonal

and \(C(A)^\perp = N(A^\top)\)

Similarly, \(N(A)\) and \(C(A^\top)\) are orthogonal

and \(N(A)^\perp = C(A^\top)\)

We can prove this easily.

Let \(x\in C(A), y\in N(A^\top)\). Since \(x\in C(A)\), \(x = Az\) for some \(z\).

Then, \(\langle x, y\rangle = \langle Az, y\rangle = \langle z, A^\top y\rangle =

\langle z, 0\rangle = 0\)

i.e. \(x\) and \(y\) are orthogonal.

Showing \(N(A)\) and \(C(A^\top)\) are orthogonal is the same.

Solving \(A\hat{x} = b\)

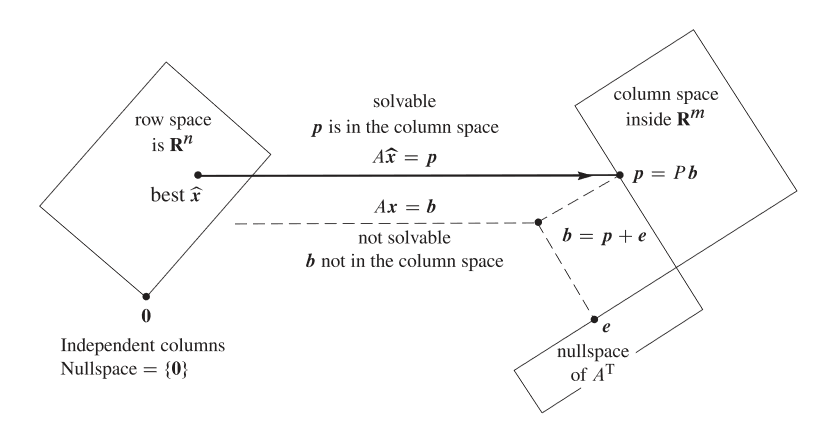

A helpful picture to see what's happening

Given any value \(x\in\mathbb{R}^m\), we can uniquely represent \(x\) with

\(x = p + e\) where \(p\in C(A), e\in N(A^\top)\) since \(\mathbb{R}^m\)

can be split up into these two orthogonal subspaces.

Geometrically, we can see that \(A\hat{x} = p\) is the desired solution we want

to the least squared problem.

Now we must figure out a way to solve for \(A\hat{x}\). Notice that we have determined that \(b = A\hat{x} + e\) where \(A\hat{x}\in C(A)\) and \(e\in N(A^\top)\). Since \(A\hat{x}\) and \(b\) differ only by \(e\in N(A^\top)\), \(A^\top A\hat{x} = A^\top b\).

When the matrix \(A\) has rank \(n\), then it has a trivial null space, and

sends non-zero vectors to non-zero vectors.

Since \(C(A)^\perp = N(A^\top)\), \(A^\top\) sends vectors in \(C(A)\)

to non-zero vectors in \(\mathbb{R}^n\).

i.e. \(A^\top A(\mathbb{R}^n)\) is a vector space of rank \(n\) and must be \(\mathbb{R}^n\),

implying that the matrix \(A^\top A\) is invertible.

The desired solution then becomes \(\hat{x} = (A^\top A)^{-1}Ab\) and \(p = A(A^\top A)^{-1}A^\top b\), which matches our understanding.